It’s the nightmare scenario that all managers and MSLs dread. The manager is in town for a visit and the MSL has lined up a series of important KOL meetings. In meeting after meeting, discussions about newly published data are short, superficial, or absent.

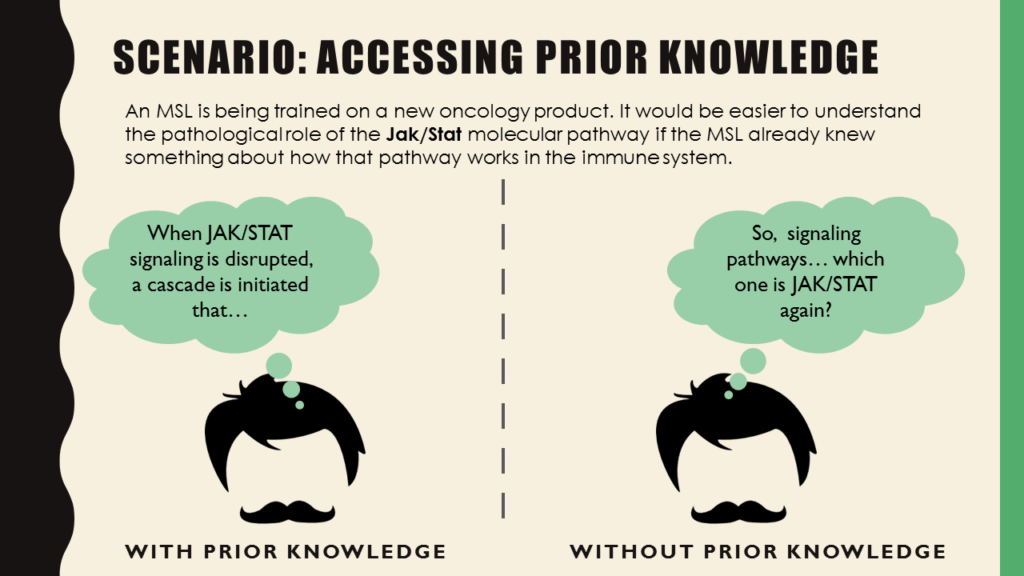

Here’s how that looks in scary thought bubbles!

Managers hire people because of what they know

Managers hire people for their teams because of prior knowledge. For example, the manager of an MSL team will make choices depending on the needs of the team at that moment. The manager may look for a candidate with prior knowledge of and expertise in:

- A disease

- The pharmaceutical industry or a specific field in the industry

- Job skills critical to the MSL role (working remotely isn’t as easy or fun as office-based people think it is!)

- A competitor product

- The type of academic training (PhD, PharmD, MD)

So many types of prior knowledge are required to be a successful MSL. In the interview process, the manager tries (with varying levels of success) to determine if the individual has sufficient prerequisite knowledge to be successful in the role.

MSLs must acquire new information continuously; it’s just part of the job. While some of the steady flow of information can be archived for later retrieval (e.g., therapeutic data), some information is critical for ongoing productivity and performance (e.g., written and verbal communication skills).

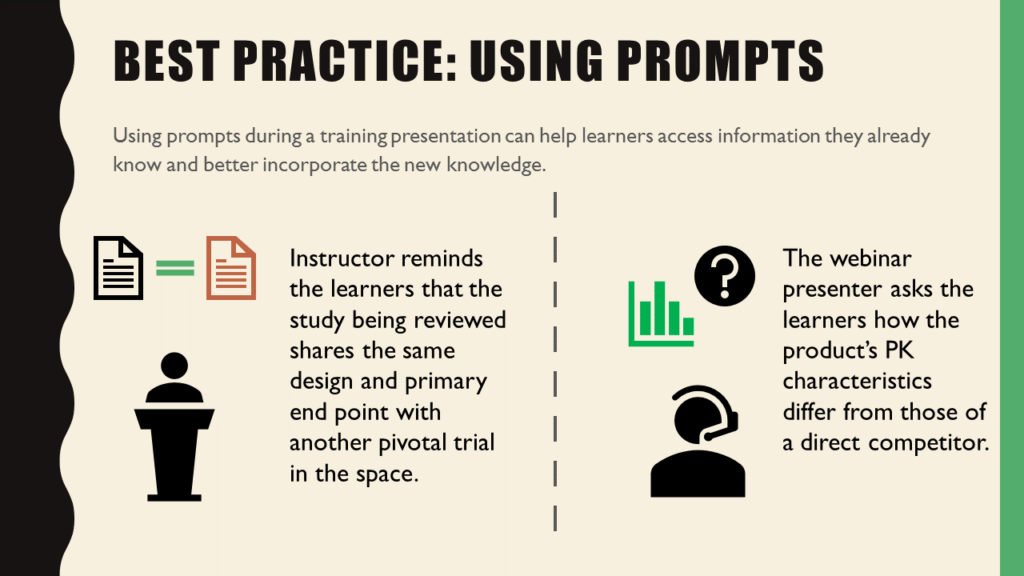

MSLs need to gauge how and when to use the information they receive. Training programs can and should do more than simply impart the new information – they should also help learners to decide when and how to use it appropriately and to greatest effect.

Training Instills Knowledge

Completion of training presumes that the learner has acquired the correct information and that it’s now stored in his or her memory. And for highly competitive and skilled teams, that’s usually true. Following a training, managers often assume that the requisite knowledge has been learned and will be applied appropriately. However, there are exceptions.

If asked, the MSL may assure the manager that the data, discussion points, and potential areas of contention are all crystal clear. And how often is that question even asked? Asking those kinds of questions can be interpreted as a lack of trust and thus may be avoided by both the manager and direct report.

In the opening scenario, the manager watched the MSL engage in KOL discussions and fail to share key data despite openings from the KOLs. In other instances, an MSL may share incomplete information. In the best-case scenario, the problem is identified and remedied, but what happens when it’s never identified?

What impact does that have on relationships in the field? Does the KOL stop meeting with the MSL because he or she has nothing to offer? Does the KOL perceive the MSL to be biased in favor of the company’s product because only certain data have been shared?

Failing to Capitalize on Prior Knowledge

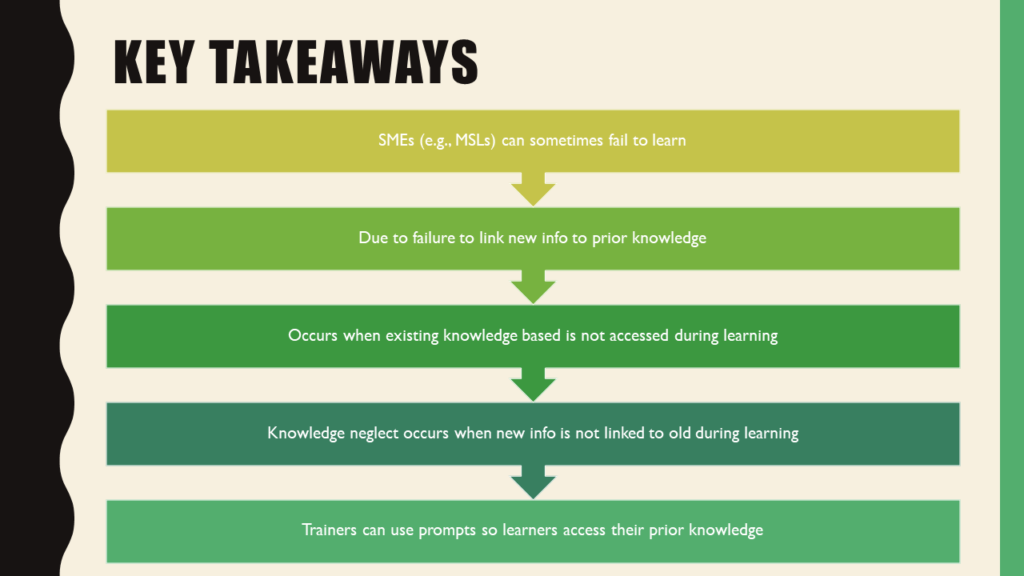

There are many potential underlying causes that might prevent an MSL from discussing newly learned information. In this instance, we are going to blame it on failure to capitalize on prior knowledge during a learning experience. We will explore other potential causes in separate blogs.

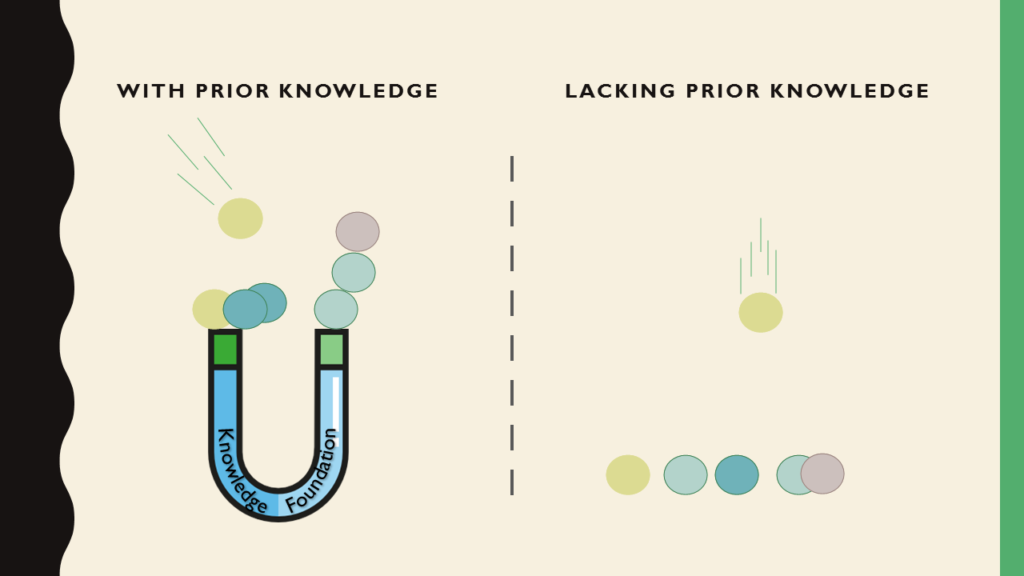

In this situation, even though the MSL completed training, the ability to retrieve it during a conversation was impaired. One potential reason is a failure to link new information to prior knowledge. In other words, the MSL did not incorporate the new training into the existing body of knowledge already in his/her possession.

New information ‘sticks’ better because it can stick to prior knowledge.

Knowledge Neglect

There’s an extra consequence to consider when a learner does not make the link between new information and old. It increases the likelihood that a learner will overlook contradictions and inconsistencies in the new data and may even miss outright errors during a discussion or learning experience. Researchers call this knowledge neglect.

In cases of knowledge neglect, stored information that would have helped the learner recognize a contradiction and/or error is not accessed and the learner accepts the new information as presented. As this phenomenon reveals, expertise in a subject is valuable, but doesn’t always prevent mistakes and may even increase their frequency in some instances.

Research suggests that heuristics are often applied in the time of need instead of direct retrieval of information from memory. In the busy and fast-paced environment of Medical Affairs, it’s possible that this happens more than occasionally.

Consider an MSL in a small group discussion with KOLs. A KOL states something that the MSL knows is untrue, but no one reacts or calls out the issue in real-time. Yes, sometimes this is because an MSL does not want to embarrass or contradict a KOL in front of colleagues. And the MSL might be right: it’s subjective and situation-dependent.

But in this scenario, that’s not what’s going on. It’s only later, when writing up notes on the meeting, that the MSL realizes that the KOL made an inaccurate statement. Because the MSL was not accessing his/her existing knowledge base while listening to the KOL, the error went uncorrected.

Was it a mistake? Was the KOL misinformed? Should the MSL bring it up in the next visit? Is it better to never mention it again? Had the MSL been deep in the pit of knowledge neglect, these questions would not have to be considered.

In future blogs, we will explore more solutions to this issue and will explore other potential reasons why an associate doesn’t retrieve and communicate newly acquired knowledge.

References:

- National Research Council, How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School (Expanded Edition). 2000, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

- Ambrose, S.A., et al., How Learning Works: 7 Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching. 1st ed. 2010, San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Bransford, J.D. and M.K. Johnson, Contextual Prerequisites for Understanding: Some Investigations of Comprehension and Recall. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 1972. 11(6): p. 717-726.

- Resnick, L.B., Mathematics and Science Learning; A New Conception. Science, 1983. 220(4596): p. 477-478.

- Cantor, A.D. and E.J. Marsh, Expertise effects in the Moses illusion: detecting contradictions with stored knowledge. Memory, 2017. 25(2): p. 220-230.